Key Points from Lectures by Jason Spicer and Trebor Scholz (Platform Co-op School 2023)

A Discussion of Scale

Key Points from the lectures by Jason Spicer and Trebor Scholz.

Jason Spicer

- Jason Spicer (JS) explains economies of scale with a comparison of making two cookies versus a dozen cookies. Fixed costs are spread over a larger number of products as production increases, resulting in lower marginal costs per unit. Marginal costs increase dramatically if production becomes too large, leading to an increase in average costs. Finding the optimal scale of production is crucial for efficiency. Achieving an appropriate level of scale is necessary for responsible production that encourages human flourishing and development.

- JS argues that small local scale is not necessarily superior to large-scale organizations. The concept of local scale can be conflated with localism. He suggests that larger employers may have better systems and processes in place to treat their workers well and can also be targets for work or organizing. Additionally, he shares his personal experiences with small employers who have not necessarily acted in a responsible or ethical manner.

- Spicer highlights three different approaches to community economic development in response to neoliberalism and globalization. He notes that small and local approaches often simply oppose large global scale, while cooperative development strategies more explicitly oppose neoliberalism. However, they have a mixed stance on globalization and focus on engaging in alter globalization rooted in cooperative and shared values.

- Jason Spicer expresses his frustration with the resistance to embracing the idea of scale, for instance, the resistance to consider establishing a company that can provide stable employment for low-income or working individuals. From his perspective and that of many working people he knows, the idea that everything must be extremely small and that any discussion of efficiency or economies of scale is suspect is simply a luxury.

- Avoiding scale can come at a cost, as failing to reach a minimum scale required to withstand the cyclical waves of firm creation and destruction can make it more challenging for future generations of potential collaborators to discover and adopt the model.

- Economies of scale tend to be most pronounced where fixed upfront costs are high, such as renewable energy infrastructure, airplanes, and rail cars, and where marginal costs are very low or zero, such as in television and video broadcasting.

- JS explains that mergers and acquisitions were not typically an option for cooperatives to achieve scale. Instead, cooperatives have historically sought to achieve scale through other means such as experimentation and innovation, though this is changing today with some new co-op merger and acquisition approaches.

- In scaling up, cooperatives face a loss of democracy or voice at scale, similar to traditional businesses. To address this, cooperatives can federate while keeping decision-making and autonomy at lower levels.

- In scaling up, cooperatives face a loss of democracy or voice at scale, similar to traditional businesses. To address this, cooperatives can federate while keeping decision-making and autonomy at lower levels.

- Because governments don’t always have the same up-front incentive to harmonize tax/enabling laws to accommodate co-ops as they do investor-owned firms, cooperatives are sometimes left to operate in a less supportive policy environment, which can make it harder for them to scale up and compete with traditional investor-owned firms, limiting their potential impact on the economy and society.

- The key takeaway is that even a good business idea cannot achieve scale if it operates in a policy context where there is no systematic support for cooperatives.

==

Trebor Scholz (TS)

- Scholz laid out definitions of scaling, asking participants to get their terms straight. Scaling, he said, is often misunderstood as a business having to operate in more countries, reaching more and more customers. Instead, he distinguishes between scaling up, which refers to increasing size and operation, and scaling deep, which involves deepening relationships and the qualities of relationships within organizations through care practices. He also mentions the conglomerate route, which he refers to as scaling out.

- The global platform cooperative community is generally in strong support of scaling up, but it is important to understand that not all platform co-ops need to be global.

- When discussing the potential for scaling up platform co-op models, Scholz argues, many tend to frame the conversation in terms of their ability to dismantle large tech companies. Such an “Uber killer” perspective is commonly found in academic literature and journalistic articles alike, but this is limiting framing. The statement that platform cooperatives may not be able to quickly dismantle large tech companies is the correct answer to the wrong question. Instead of focusing solely on replacing large tech companies, it is important to acknowledge that platform cooperatives can (and do) offer valuable alternatives that prioritize the shared interests of their workers, users, and communities. Platform cooperatives come in various shapes and sizes, and they have the potential to create value in different ways in various industries. It’s not an either/or situation where they have to either destroy existing corporate platforms or be deemed worthless.

- It is important to understand the value that they are contributing and not merely reduce the discussion about scale to a zero-sum game.

- Many existing platform companies rely on minoritized, low-wage workers who often face unfair working conditions. By scaling up worker-owned labor platforms, Scholz believes that we can create a culture that supports equal access to just platform work, especially for low-wage and immigrant workers. While some platform co-op models may indeed outcompete their rivals, or become secondary or tertiary competitors in local markets, the primary goal of most platform cooperatives is to offer synergistic solutions to collective challenges, small or large. In New York City where Drivers Cooperative with over 9,000 onboarded drivers, for instance, is well-positioned to become a tertiary ride hailing solution. But research focused on the United States suggests that cooperatives don’t tend to outcompete large corporations; they rather co-exist.

- TS shows that throughout history, cooperatives have typically been founded to serve the needs of people who are not supported by the safety nets provided by families, communities, or markets. In industrialized countries, particularly in Europe, cooperatives have often been created as a response to state intervention or regulation. Meanwhile, in developing countries, cooperatives have arisen in the absence of adequate support from families or larger communities. It’s important to note that the raison d’être of platform cooperatives is often not to build global monopolies that kill off the competition. Rather, these cooperatives seek to improve the situation of the communities that start them.

- Trebor Scholz holds the belief that the decision to scale platform cooperatives is dependent on the specific sector and business model. For instance, sectors such as ride-hailing or short-term rental may require global scaling, while others like home services or care may not need to become digital platforms with users all over the world.

- Focusing on practical lessons for platform cooperatives Scholz offers nine aspects, strategies, and considerations for scaling platform cooperatives. These include leveraging shared digital infrastructure through federations and social franchises, replication of existing models with local adaptations, conversion of startups into community ownership through trust buyouts and tokenization, exploring distributed technology such as web3 prototypes, and creating globally distributed platform cooperatives. Regulation, supportive grassroots movements, alliances with social and political organizations, legal structures, the need for a supportive international ecosystem ( all along value-aligned supply chains), and the role of cooperative development institutions and anchor institutions are all key factors that can impact the scaling of platform cooperatives. By considering these factors, platform cooperatives can foster a culture of cooperation and mutual aid, achieve growth and impact.

- The vision behind scaling platform cooperatives, for Scholz, is not to create an economy dominated solely by cooperatives, but rather a diverse range of organizations, including independent worker- and user-managed enterprises, both platform-based and not, up and down the supply chain. As a supporter of a “bricolage of organizations”, I recognize the importance of various organizational models such as social enterprises, community organizations, and publicly owned entities, alongside cooperatives.

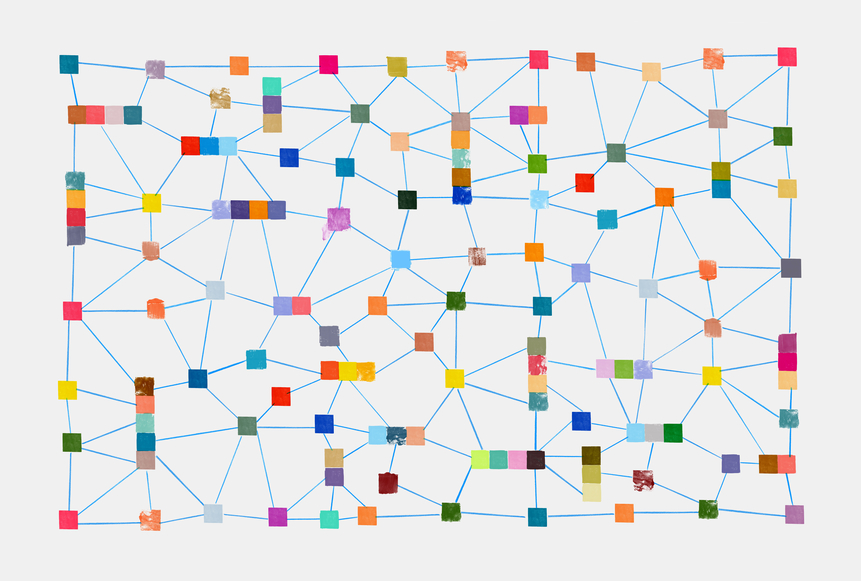

- This vision prioritizes a pluralistic digital commonwealth approach that recognizes different sectors may demand different structures and sizes of cooperative enterprises. It is a vision of a digital Cooperative Commonwealth network of small autonomous interlinked but competing co-ops. In the United States, this goes back to the Knights of Labor fought for a multiracial cooperative commonwealth as early as the 1880s And of course there is a long utopian socialist lineage from Henri de Saint Simon to Robert Owen that evoked a global federation of cooperative communities. This approach fosters a more diverse and resilient economy that is responsive to the needs of communities and supportive of multiple models of enterprise.