The Solidarity Stack

[I delivered this keynote at the Cooperative AI Conference in Istanbul on November 11, 2025, as part of the Platform Cooperativism Consortium’s annual convening, addressing the stakes of AI governance, cooperative digital infrastructure, and worker-led alternatives to extractive platform systems.]

Convening events like this—our eleventh PCC conference—usually means last-minute visa cancellations and frantic edits to the printed program. By the time I sit down to think about my own talk, it’s somewhere between airports, running on no sleep and too much coffee. But there’s always that shared sense of purpose that I feel. The feeling of solidarity that keeps me going.

As many of you know, I’m coming here from New York City.

Who has ever been to NYC?

And how many have taken one of those famous yellow cabs?

Then you’ll know what I mean when I take you—just for a moment—to Queens.

This is where Nicanor Ochisor drove his yellow cab. Perhaps you even rode with him once. Here’s a photo—maybe you remember him.

He told his friends he felt too old. “I’m tired. I can’t do it anymore.”

He paid his bills, hung his jacket on the chair, set his phone on the table.

In that small garage in Maspeth, Queens, he looped a rope over a beam and ended his life.

For almost thirty years, that yellow cab never stopped moving.

At sunset, Nicanor took the wheel. He drove through the night—rain, snow, empty streets.

At dawn, he parked the cab, handed the keys to his wife, and

she drove through the day.

They built their lives around that car, one shift ending as the other began.

Then everything collapsed. The taxi license that once cost nearly a million dollars became almost worthless as Uber’s stock soared.

Debt pressed on his chest like a weight he couldn’t lift.

What killed Nicanor wasn’t only debt—it was isolation.

Yet in these crises, people do what they have always done: they turn to each other — because hope is not wishy-washy; it’s a decision, to work together and build something different.

So, what if the future of digital platforms and AI didn’t belong to just a few companies but to global movements—workers, farmers, educators, and technologists—

building tools that reflect their own needs, cultures, and values?

Nicanor’s story reminded me of my own first encounter with a system that demanded obedience—the East German state.

I’ve never shared this publicly: When I was 17 in East Germany, my father came home. I had never seen him that angry. “You’re on their list of the 100 most ‘aggressive state enemies’ in East Berlin,” he said with squinting eyes. The Secret Service had visited him.

Sitting really far apart in a big living room, my mother cried, terrified for my future: the prospect of no college, menial jobs, maybe prison. But got me through this?

Well, I remember standing on Alexanderplatz with friends, protesting, scared out of our minds. And yet, what held us together was that really warm feeling of belonging and solidarity. We were each other’s hope.

Two years later, the wall came down—because people like us had turned toward each other.

It was a very similar feeling many years later as a professor in New York when I began studying people who work online, first the microtaskers and later the drivers, couriers, data labelers, content moderators, really millions of people laboring in isolation, often invisible to the systems they sustain, and there are anywhere between 405 and 435 million such workers today worldwide.

***

One night, in the eleventh hour of a conference, a worker from Seattle stood up and asked, “What if we start our own digital platforms?” That question was the spark.

I stayed up late, sketching a framework for an Uber owned by its drivers—a vision I came to call platform cooperatives. By morning, tens of thousands had read it.

What began as a concept became a global movement. Together, we map concrete pathways for action and identify resources in our networks: a handful of coders in Paris building a federation; drivers in New York City rewriting an app line by line.

There were two approaches: some aimed to transform entire sectors, others focused on feeding their families. There were countless painful failures and burnouts, but also real successes that kept the work moving forward.

Today, more than 1.2 million workers in 53 countries are working in the cooperative digital economy. But of course, one million out of 435 million is still just a drop in the ocean—but it’s a start, a proof of concept that cooperation can grow.

I didn’t seek to lead—it found me, as people around the world began reaching out, determined to build platform cooperatives of their own.

And they still do 10 years later. From Ghana and Tanzania to Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Argentina, the idea traveled through networks of solidarity. What began as a sketch on paper has become a collective act of imagination, carried by countless others.

This work has also started a new academic subfield that is deeply interdisciplinary and really looking at theory after praxis.

Through the Platform Cooperativism Consortium and the Institute for the Cooperative Digital Economy at The New School, and the work of many colleagues, we’ve built the backbone for this work, connecting researchers and practitioners from São Paulo to Seoul, Nairobi to New York.

Our work as researchers at The New School is guided by impact on communities, not by academic prestige. We do not measure success by citations or journal rankings but by how people’s lives improve.

At the ICDE, 58 PhD students and dozens of fellows—Morshed, Tara, Stefano, Dorleta, Stefan, and many others—carry this approach forward, treating research as a tool for practice and collaboration, linking ideas with lived experience to strengthen the cooperative and solidarity movement from the ground up.

Platform cooperatives keep growing, some small and local, others at scale. The challenges are real, but they persist. What we see now isn’t the hype of the early days, but something steadier, less flashy, and more real: a quiet mainstreaming of cooperative models into digital life.

New forms continue to emerge– from worker-owned platforms and technology to data cooperatives.

If the first decade of platform cooperatives was about proof of concept, the next will be about fearless expansion—about refusing to be sidelined or absorbed.

Yes, the obstacles are real, we acknowledged that, but this movement will not be defeated. We will double down: on experimentation, on global reach, on building the infrastructures of solidarity that Big Tech cannot imagine.

Also PCC will grow stronger, anchoring new research and alliances across Asia, Africa, and beyond.

And that brings us here—to this gathering.

Friends,

In this room are researchers, organizers, activists, workers, and educators from nearly 30 countries. Some write poems. Some plant seeds. Some write laws. You did not HAVE to be here. You are here, and I’m here.

You could be sipping a double espresso at a café in Paris, or collecting chestnuts with your kids in the Grunewald in Berlin, or you shop at Kadıköy [KAH-dih-koy] market here in Istanbul.

But no: YOU ARE HERE because you decided to be here because of this community of value to which you belong and to which I also belong– the cooperative community.

A community that refuses despair, and insists that the digital future can serve the many, not the few.

This movement is about people like Kauna, whom I met in Mombasa last fall—her voice trembling as she spoke of content moderators in Kenya and Nigeria, exploited by OpenAI and Facebook, forced to sift through violence and hate for a few dollars a day.

It’s about Akkanut, who stands beside riders whose fingers are bruised from gripping delivery-bike handlebars in Bangkok’s sweltering heat and Phuket’s flash floods.

It’s about Ganesh in Kerala, supporting e-hailing drivers as their phones buzz with canceled rides in the choking traffic of Kochi. Or Terence who came here from Hong Kong.

And it’s about Mehmet, who told me—with a trembling voice—how NeedsMap helped people after the 2023 earthquake: delivering 10,000 tents and blankets and finding homes for thousands displaced. NeedsMap is a real expression of imece [ee-MEH-jeh]—that spirit of solidarity that saved lives when institutions failed.

Together, these stories trace the outline of a movement. One that is based on hope.

It’s about Melissa, whose AI cooperative digitizes Jeremy Bentham’s handwriting—refusing Big Tech buyouts and proving that integrity can be quiet and world-changing.

It’s about Austin and Felix, whose projects faltered but whose persistence became the compost for new growth.

Because movements are living systems. They shed, they decay, they renew. Each closing co-op, each unfinished experiment becomes soil from which the next begins to grow.

It’s about Kaya, who exposes how “national moral AI” in Turkey mirrors existing hierarchies, erasing women, Kurds, Alevis [AH-leh-vees], queer and trans communities, and refugees.

It’s about Abeba, Antonio, and Rafael, who uncover bias, trace invisible labor, and bring intersectional perspectives into cooperative research.

Different cities, different struggles.

We come from social enterprises, cooperatives, universities, and computer labs—but we share one conviction: that the future of AI and society must be grounded in solidarity.

***

So, in a way, my talk offers an umbrella for the many conversations you’ll hear over the next four days.

You’ll hear about cooperative data centers like the one in Ashton, UK, that Tara Merk will present, and you can even imagine your own community data center with her. You’ll hear about one of the first AI cooperative: Transkribus.

This work unfolds amid a growing crisis of dependency—the quiet realization that the infrastructures of artificial intelligence are anything but neutral.

Unregulated AI oligopolies now threaten democracy, innovation, and even security.

AI today operates through a vertically integrated stack—hardware, cloud infrastructure, models, labor, and applications—each layer concentrated in the hands of a few firms.

From AWS shutdowns that lock people out of their homes to a South Korean data center fire that erased 800 terabytes of public records, to AIs trained on invisible Global South labor—the same logic runs through it all: technologies built for extraction, concentration, and control, not for people or democracy.

Nvidia designs nearly all specialized computer chips; its market value now exceeds Germany’s annual GDP. And even if an EU AI Stack—or one day, an African regional equivalent—were to become reality, it would still depend on chips from Nvidia.

AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud dominate computation and storage, including military and surveillance applications. The model layer—through APIs and proprietary datasets—reproduces algorithmic bias and dictates who can build and who must merely consume.

Even the application layer—from chatbots to image generators—relies on this controlled pipeline, burning electricity and consuming about a liter of water per query.

***

SO, PEOPLE DO WONDER WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT:

Thousands of “people-centered AI” policies exist, yet authoritarianism and austerity are spreading.

Political will and funding remain far below what’s needed to build a solidarity-oriented AI. Even when laws are passed, enforcement is rare.

The EU Stack project comes too late—and rests on the fiction that policymakers are uniformly leftist and ready to act.

Legislation and unions are indispensable, but they’re not enough. Law reflects political will, and in more than 130 countries under austerity measures, that will is constrained. Real change cannot come from the top down alone. It also has to rise from below—from workers, communities, social movements, and cooperatives building new forms of power in their own image.

What’s needed is a bricolage of efforts that combine policy, worker representation, and cooperative practice. Because no single instrument—not law, not regulation—can counter structural power on its own. Not anymore.

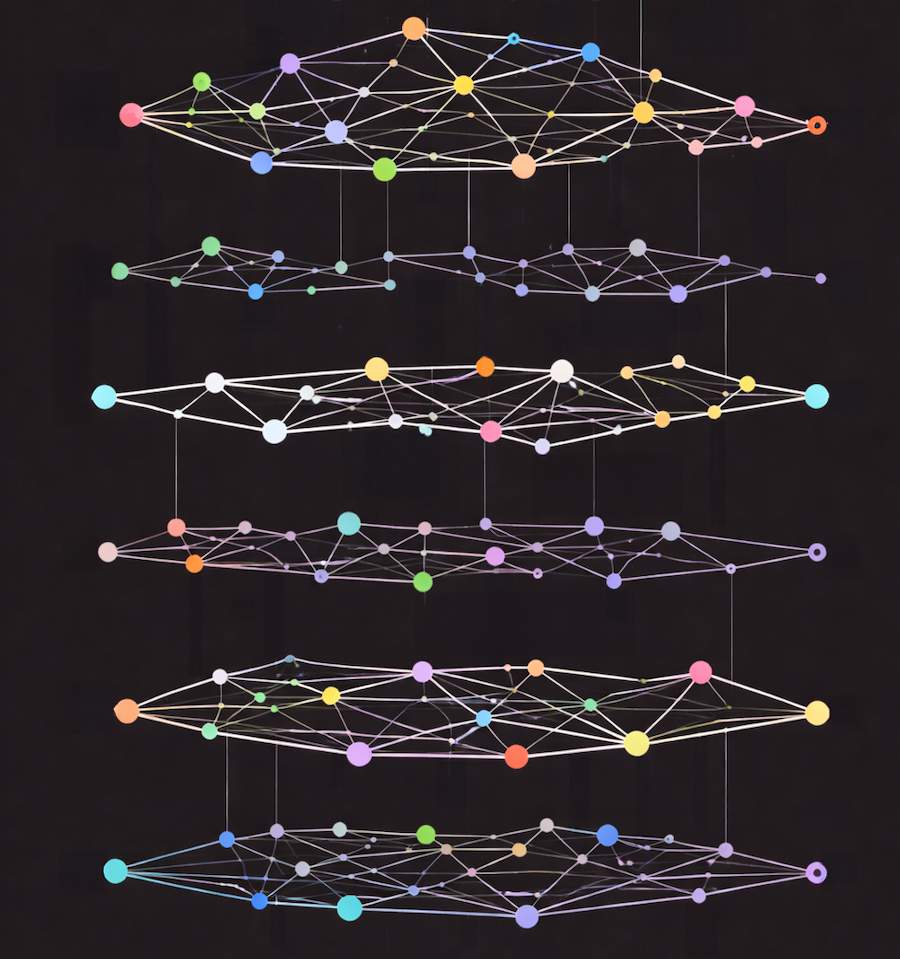

Our task is to reclaim that power and to build the alternative—what Morshed Mannan and I call the Solidarity Stack, showing how cooperation can reclaim AI—layer by layer, from the Earth to the Cloud.

The Solidarity Stack offers a cooperative counter-architecture, a system of ownership and governance stretching across every layer of the AI ecosystem, from the earth to the cloud. It is built bottom up.

Over the past ten years, we’ve learned that federations of platform cooperatives are most powerful in specific local contexts—among LGBTQ+ workers, among women of lower caste, among migrant couriers in many countries earning only a few dollars a day.

We’ve also learned from data cooperatives and cooperative data trusts, from recuperated factories, food and housing co-ops, from large profit-oriented cooperatives, from union-coops organizing gig workers, and democratic ESOPs that extend ownership and voice to workers.

What has become clear is that, while each of these efforts matters, none of them alone can bring about deep social transformation. And now, planetary ecosystem thinking is indispensable. To do that, we have to think of them together—as parts of a larger system, a stack of solidarity.

Global associations and organizations representing cooperatives have a vital historical role, but they are not vehicles for the kind of coordinated, bottom-up action needed to build this new stack. Their frameworks were designed for another era; the Solidarity Stack requires more porous, experimental alliances that can move across sectors, borders, and technologies.

And one of the very big lessons was that the main problem in developing those alternatives are often not technological, but they are about people, right? They are often a collective action problem.

***

The Solidarity Stack offers a horizontal ecosystem linking cooperatives, social movements, and recuperated factories, where every layer of the AI world—from the earth to the cloud, from the rare-earth mine to the algorithm—is collectively owned and governed, bound by a shared commitment to mutual care, justice, and collective autonomy.

The Solidarity Stack is not a utopia but a real utopia: the dots already exist—from cooperative data centers and to federated platform co-ops and community-built AI models—and connecting them into a cross-border system of solidarity is the only way for cooperatives, even the largest ones, to escape extractive supply chains and create shared value across the entire digital ecosystem.

The Solidarity Stack

At the foundation—the Earth layer—we begin with what makes computation possible: lithium crystallizing on blinding salt flats under a sun that burns the eyes, cobalt hacked from red earth by hand, and rare earths blasted from rock that fills the lungs with metal dust. Cooperative mines and renewable-energy commons in Colombia, Chile, South Africa, and Austria show that even these raw materials—and the energy that smelts and powers them—can be organized as shared resources rather than sites of extraction.

Next comes Digital Infrastructure: the hum of servers and the pulse of cooling fans inside community-owned data centers like Hostsharing eG in Germany or the Ashton Data Center Cooperative in the UK.

At the Data layer, personal information becomes a shared resource rather than a private commodity. In Zurich, a teacher gathers the traces of her days—Fitbit steps from morning walks to class, grocery payments from her bank app, iPhone location trails, years of clinic records—into a single MyData account she controls. What once meant opaque extraction now feels tangible: the soft click of toggling permissions, the small satisfaction of seeing data flow toward care instead of profit—turning surveillance into participation.

At the Algorithmic Development layer, code itself becomes a site of cooperation. Tech co-ops like Facttic in Argentina, Outlandish in London, and Patio in Barcelona are democratic enterprises—workplaces that reflect the values of their members. They write code collectively, deciding together what to build and why. In doing so, they give dignity to the people who work in them and align technological practice with social and environmental imperatives.

At the Labor layer, the hidden workforce behind AI comes into focus—coders, content moderators, data labelers, and annotators who spend long hours training datasets, filtering violence and hate, and debugging systems for a few dollars a day. Scattered across Nairobi, Manila, and Bogotá, they sit at glowing screens that feed the global machine. From these same workers, new cooperatives are emerging—turning precarious digital piecework into collective power.

At the Application layer, there are cooperatives in agriculture and banking. They are already adopting it—credit unions using AI to speed up loan approvals, farm co-ops optimizing yields and logistics. In Brazil, Sicredi Ouro Verde MT’s AI copilots free time for member engagement, and in Denmark, Arla Foods uses cooperative forecasting to reduce waste. Yet the question is whether these tools deepen dependency on corporate AI and data extraction, or whether cooperatives, working together, can build systems true to their principles—transparent, autonomous, and accountable to their members rather than the market.

At the Model and User layer, AI systems and people meet—not just as users, but as co-governors of how intelligence is trained and applied. In Mombasa, Kauna Malgwi, a Nigerian content moderator, helped found the African Tech Worker Cooperative after suing Meta and Sama for unsafe working conditions. The co-op now unites moderators, data labelers, and engineers to train locally grounded, worker-owned AI models—turning invisible labor into collective power.

And then, at the Governance layer, the question is how such a stack could be governed internationally. Democratic oversight must ensure transparency, accountability, and participation across federated systems. Some look to Project Cybersyn in Chile or the Soviet cybernetic experiments of the late 1950s—the first attempts to manage complex economies through networks—and others to today’s democratic DAOs for inspiration. We can also look to the SWIFT network, a cooperative of financial institutions that already links thousands across borders, showing that global protocols and data layers can operate on cooperative terms.

Beneath every layer of the Solidarity Stack lies what AbdouMaliq Simone called people as infrastructure: the human networks of trust, improvisation, and mutual care that keep systems alive when formal structures falter. However advanced the technology, it is these human circuits—people becoming infrastructure for one another—that give the system its pulse.

***

Friends, after 10 years of this work, one thing stands out:

It’s really about people.

It’s about you.

Every one of us in this room is part of the Solidarity Stack.

The question is: what will we do with it?

Because the AI crisis won’t be solved by laws or better code alone.

It will be solved by people — by you — organizing across layers, borders, and disciplines. Across the stack.

That’s why I’m asking you to start Solidarity Stack Circles — small groups of three or four people, maybe the ones you’ll have dinner or drinks with tonight.

People who will keep working together after this conference — not just talking, but building something together: a culturally specific language model, a multilingual AI agent, a story project about how workers use AI, or any small initiative that explores solidarity in the digital economy.

Later, through the global course we’ll host in 2026, these circles will come together — connecting their projects and shaping what could grow into a democratic organization capable of leading collective action on the Solidarity Stack.

You don’t need to be an expert to begin. So, I am asking you to sign up by 8 PM tonight if you want to be part of that effort.

But you do need to start a circle — because the answer is always other people.

Each circle will be a small act of cooperation, and next year, we’ll connect them through a global online course — a space to share progress, support projects, and grow this movement. Out of that, we’ll begin forming a democratic organization capable of leading collective, planetary action on cooperative AI. But if we don’t act — if we leave here inspired but unconnected — then the authoritarian stack will dig in deeper, and cooperatives will adapt to Big AI instead of transforming it.

I’ll end by saying, like, if you care about solidarity, and if you agree with me that something needs to be done, then I’m asking you to please add your name here, and we will follow up to start building a network for action that perhaps one day can grow into a democratic organization that can lead this work on a solidarity stack, across social movements, across the co-op networks, platform coop federations, across academia and social enterprises. It has to be planetary, and it has to be now. So, I’m urging you to join now.