The User Experience in Platform Cooperativism

Some thoughts on the design of collaborative platforms and reputation systems that make it possible to build trust and solidarity networks.

“Platform Cooperativism” is a fairly recent concept coined by Trebor Scholz and Nathan Schneider to disrupt the collaborative economy scenario, which is currently dominated by a few “unicorn” corporations and by what many people consider a neo-capitalist perspective. The concept is particularly timely because it coincides with the emergence of new proposals linked to the Social and Solidarity Economy that review the links between the economy, society and democracy, both inside and outside organizations. The concept of platform cooperativism can connect the tradition of free software (from a digital Commons perspective) with the current demands of “crowd-workers” affected by extractive versions of the Sharing Economy.

In light of the recently published guidebook Ours to Hack and to Own, edited by Trebor Scholz and Nathan Schneider, and the Platform Cooperativism 2016: Building the Cooperative Internet conference held recently in New York, this article aims to summarize a few approaches related to the design, user experience and co-creation of digital cooperative platforms. It focuses on an explorative research session that we facilitated during the accompanying “unconference”, which gave rise to a series of potential lines of action related to online reputation systems for platform coops.

From crowd-workers & followers, to cooperativists & owners

As Scholz and Schneider point out in Ours to Hack and to Own, platform cooperativism emerges at the intersection of shared governance and shared ownership. Technology should be an opportunity to broaden the scope of organizations based on the Rochdale Principles (which were first set out in 1844 to boost the social and economic impact of these organizations). Similarly, Scholz argues, modern digital platforms should be inspired by the cooperative movement and based on the principles of democracy and self-management. These new technological structures should embed their values and support local economies. Thus, platform cooperativism should be a response to the “new industrial renaissance” —to quote Douglas Ruskoff—, which is currently controlled and centralized by small number of companies, generating a new digital capitalism in which workers and users are merely followers.

In Ours to Hack and to Own, Mckenzie Wark discusses the vectoral political economy, in which most information is private property, and which is in many respects worse than the capitalist political economy. It is what Steven Hill calls a “freelance society” made up of “crowd-workers” threatened by an “un-sharing economy”. According to labour organizer Kati Sipp, labour assessment of people who work in the cooperative platform and reputation-based economy should incorporate the best practices of the collaborative economy. Digital technology based on cooperativism should contribute to eliminating inequities for the people involved. In the book, after analyzing three types of cases (time banks, food swaps and makerspaces) close to platform cooperativism, Juliet B. Schor stresses the key issue of inequalities related to race, class, education and gender. To prevent this, she suggests that there should ideally be a diverse group of founders and early participants.

Another important perspective – which is discussed in the collection of essays in the book and was also highlighted at the conference – can be found in the current political and economic context of Barcelona. The papers by speakers like Mayo Fuster and Francesca Bria brought up critical issues such as technological sovereignty, gender balance, transparent governance and other challenges in the co-creation of public policies, at this crossroad between the social economy and the sharing economy.

Community-centered design, lean platform co-development and open source

Along similar lines, during the “How to Build Platform Coops” panel organized by Sasha Constanza-Chok (Civic Media MIT & rad.cat), Una Lee spoke about community-centered design processes and the concept of “design justice”: how to design with and within communities in such a way as to advance social justice. This tactical approach to developing platforms and interfaces connects design practitioners with people who have been historically marginalized by design, in order to radically collaborate with them in building relationships leading to the creation of platforms, processes, and systems that will ultimately have an impact on their lives. An example: the action research and facilitation work carried out by the team behind contratados.org to uncover the actors and processes in low-wage labour recruitment along the Mexico-U.S. migrant stream.

Another key element discussed in the same panel focused on the need to adopt and incorporate strategies from the lean startup approach (on which the majority of big, extractive “sharing economy” platforms such as Uber and AirBnB are based). An important aspect of the ”lean” methodology is the fact that it also represents a learning process, as Evan Henshaw-Plath explains. Similarly, new platform cooperatives should also incorporate early feedback in their learning and development loops and base their growth on “minimum viable platforms” modularly built around user experience. This approach is similar to the analysis set out in the foreword of this review of methodologies carried out by Dimmons for the design and incubation of collaborative platforms, which also points out the need to identify and scale up new ways of funding platform coops (other than aggressive “business angels” and other highly speculative formulas).

Another key element discussed by this panel was the importance of the open source philosophy: when platforms based on cooperativism appropriate the strategic “lean development” used by their “extractive” competitors, open source and the ethos of the Free Software movement seems to be the right approach and the way forward. At the conference, Drutopia activist Micky Metts remembered how Richard Stallman harnessed the hacker culture tradition of the 1970s to launch the GNU Project. As Paola Villareal pointed out, open standards (such as oHail, an API standard for ride-hailing services) are a basic element for engaging more people in building truly open cooperative technology platforms.

What if the “cooperativist UX” adopts open badges for a fair reputation system?

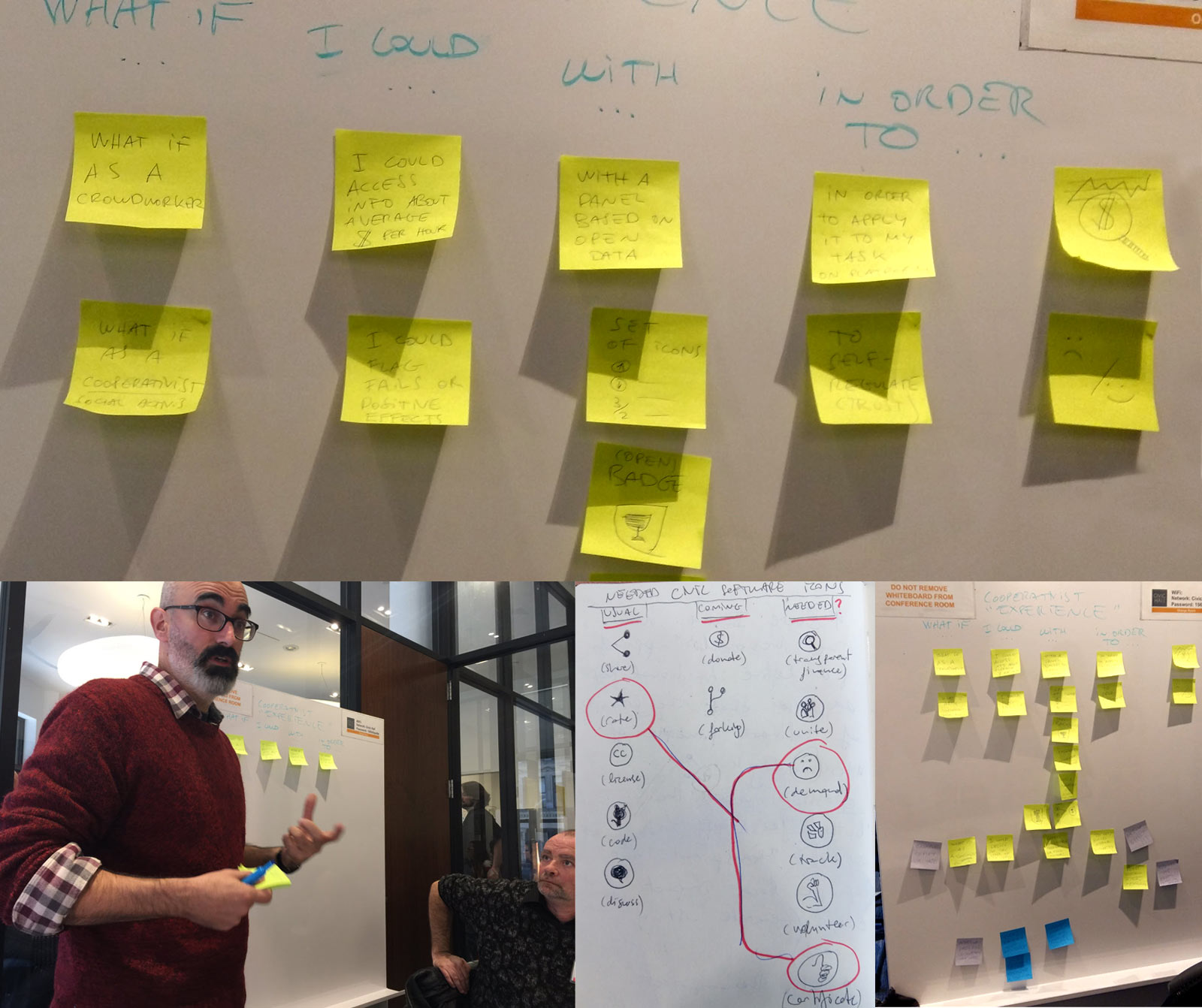

Following this panel at the conference, both of the authors (Enric Senabre and Ricard Espelt) were interested in further exploring the critical issue of co-design, the user experience (UX) approach and requirements of platform coops, which we had discussed with other people from the “cooperativist UX” point of view. So we organized a short explorative session on the third day of the PlatformCoop unconference at Civic Hall, with participants from the fields of digital media and software development, social justice, community organizations and unions, all interested in the approach.

We organized a dynamic session based on a process of modularly building new user stories for platform coops in general, following a process that is often used by agile developers to identify new requirements for software. In our case, this interaction allowed us to document the discussions around different issues from the perspective of the needs and expectations of cooperativism (related to user stories and platform interfaces in general) following the research through design approach.

The results were interesting, although the session did not work exactly as we expected, given that we had intended to brainstorm and generate as many user stories as possible on different types of requirements. Instead, we began with a reflection on which specific functionalities and features (other than those available on existing online platforms and social web interfaces in general), if any, could be explored. It blocked up the session for a while, but after coming up with some missing elements that could help to generate trust in online communities related to cooperatives and unions, we finally arrived at the key element of online reputation systems for every social web application.

As we started to specify some basic definitions of a user story for cooperativist-led reputation and feedback systems, some of the examples that had been shared over the previous days at the PlatformCoop conference resonated in the discussion. Examples include the case of crowd-workers not wanting to have their photo on their online profiles, or the other side of online trust systems: when sharing economy platforms are rated by users “outside the platforms”, as on FairCrowdWork Watch; or when users can blacklist unfair requesters on microtask platforms like MTurk via the CrowdWorkers browser extension; or the example of Contratados’ employer and recruiter reviews.

But what about the positive side: building trust among platform cooperativists by transparently connecting to each other online and mutually recognising value? And what about adding openness and transparency? At this point, trying to move further, we discussed open source examples like the Wikipedia barnstars awarded to contributors for hard work and due diligence, or the digital self-assessment of an organization’s social impact used in the social and solidarity economy in Catalonia, as well as the interesting and relevant example of Mozilla’s open badges, which usually operate under the umbrella of digital learning but could also be adapted and adopted….

After drawing inspiration from imagining possible new positive rating icons (beyond the classic, limited and even pernicious standard of star rating features), we went on to discuss variations of a user story, which can be summarized in the following formula: “user + action + component + goal” (as expressed in co-design workshops by the Platoniq facilitation model):

What if as a platform cooperativist + I could mutually and independently rate and be rated + with a distributed and generative badges-like system + so I can contribute to build networked solidarity and trust.

That leads to interesting variations around user stories of this kind, which can be seen as a pattern that grows with the addition of other actions or goals related to equitable models, and can be modular and allow user control of the levels and types of personal information displayed. Although we didn’t have time to move to different potential requirements, the story allowed the group to address other key elements like:

- The importance of avoiding long and tedious forms (if the reputation system is to embrace meaningful indicators beyond stars or “likes” and “dislikes”).

- The adoption of effective peer-to-peer mechanisms at the technical level, to ensure that mutual feedback is solid and coherent.

- The need for UX design to pay attention to ensuring attractive icons and symbols to reinforce motivation.

- The fact that aggregation (and, of course. critical mass) means that individual open rating in given platforms could also be a way to dynamically rate the platforms themselves.

- The interesting issue of mutual mentoring and skills for adopting and generating these kinds of badges, as a channel for deeper understanding of the internal logic of digital platforms and how to build or improve them.

Questions for future research, and development

As a follow-up to the session, apart from this written report, we consider it important to highlight the fact that the output resonates with the research work of the Stanford Crowd Research Collective, especially in relation to the centralization and decentralization of reputation systems in “crowd guild” platforms, and the importance of considering the social dimension of sustainability when building technological systems, as set out in the KarlsKrona Manifesto.

The next steps in addressing “platform cooperativism UX” should continue along these lines: new user stories that generate both potential platform coop requirements and design-driven research outputs. In the short term, there is the upcoming Platform Coop event in London, where we believe that co-design discussions can keep contributing to advancing this new digital economic paradigm. We also hope to bring this methodology and the same questions to our local context in Barcelona, especially in relation to existing and new coops that are developing digital platforms and strategies in the emerging field of cooperative agricultural food products and possibly others.