Mapping the Cooperative Digital Economy

We love maps because they help us see the world, but every map, index, or directory goes out of date the moment we make it.

How might we make a map of the cooperative movement that lasts?

On November 7th in New York, a mix of co-op co-founders and allies – 67 people from 41 projects around the world – came together for a day-long session to map our community before the 2019 #platformcoop conference. We recognized that without facilitated valuable exchange among users, maps quickly go out of date. Our goal was not to create a new map, but to discover how and why mapping might help us.

After a day of sharing situations and needs, we framed how some map, index, or other infrastructure might help our growing community. The specific needs we prioritized were 1) to center co-op practitioners, 2) highlight key points in their stories, and 3) combine case studies with dynamic communication. And as Édith Darin of CoopCycle said, the session served as “a good introduction for the following days!”

The rest of this story is about what we did, what we learned, and what’s next in the process of co-designing some kind of community map or index. To get involved or be included, fill in the form at tinyurl.com/coopdevkit.

Why Mapping Matters

Five years ago, in 2015, the first conference about the idea of “platform cooperativism” took place at the New School in New York. It was a joyous, long-awaited gathering for people who had been struggling quietly to advance cooperative alternatives to the dominant platforms mediating gig work, accommodations, data, and content. Since then, thousands of people around the world attended the annual conferences and organized others, read and wrote books and articles, reimagined their own projects and platforms, tweeted, and waited. And in our session before the 2019 conference, we saw how this community has become a place for people to find one another. The 41 projects represented included both emerging co-ops like Mensakas, a courier-owned delivery platform in Barcelona, Spain that began in 2017 (recently featured in VICE), to established co-op projects like the Women’s Multicultural Resource and Counselling Centre of Durham (WMRCC), an anti-violence agency providing free, culturally sensitive services since 1993 near Toronto, Canada, and now incubating six co-ops to expand its work.

Today, how much new economic activity has come as a result of this community? How much potential do we as practitioners and allies have to take it further?

Clearly, our community needs a good map or index, a way to make sense of things. But, good maps and indexes are hard to find! Trebor Scholz at the New School and Jutta Treviranus at the Inclusive Design Research Centre (IDRC) recognized this and included an indexing project as part of a grant they secured from Google dot org. And in the summer of 2019, Trebor emailed me with an invitation to facilitate a community session focused on co-designing a new map/index, one that might serve a wide variety of very different stakeholders.

This invitation spoke to me. Since May Day of 2016, I’ve helped organize a dozen different gatherings about cooperative platforms. A 48-hour hackathon in Hong Kong yielded a dozen prototypes, and 3-hour unconference in San Francisco called “User, Worker, Owner” surfaced questions about scaling equitable ownership and showcased projects trying to make it happen. Over 1,200 people have come to these events from the tech, tourism, performing arts, workers rights, organized labor, civic infrastructure, and so on. In organizing these events, I’ve learned two lessons. First, including new and diverse participants requires universal questions, like asking about “equitable ownership of platforms we depend on,” before suggesting co-ops are the answer (they may be one of many!). Second, opening up collaboration among participants requires helping them find and connect with one another with few intermediaries. For me, less facilitation means more work in user researcher. When I was invited to help create infrastructure for self-organizing with a map, index, or directory, it seemed like a good idea for me, too.

So, to frame this session, I interviewed Trebor and the conference producer Michael McHugh about their situation and motivation. They talked about the overwhelming volume of emails they’ve been sorting through from freelancers and philanthropists eager to build and support cooperative alternatives. They wanted some way for people to find one another more directly and productively, and had various map and index ideas in mind. I also talked with Cheryl Li and Ned Zimmerman at the IDRC to get input on what they needed as new collaborators to begin their co-design process, as well as feedback on how this session might serve as a starting point.

The question we all converged on was simple: How might we as a community frame the real mapping or indexing problem we want to solve?

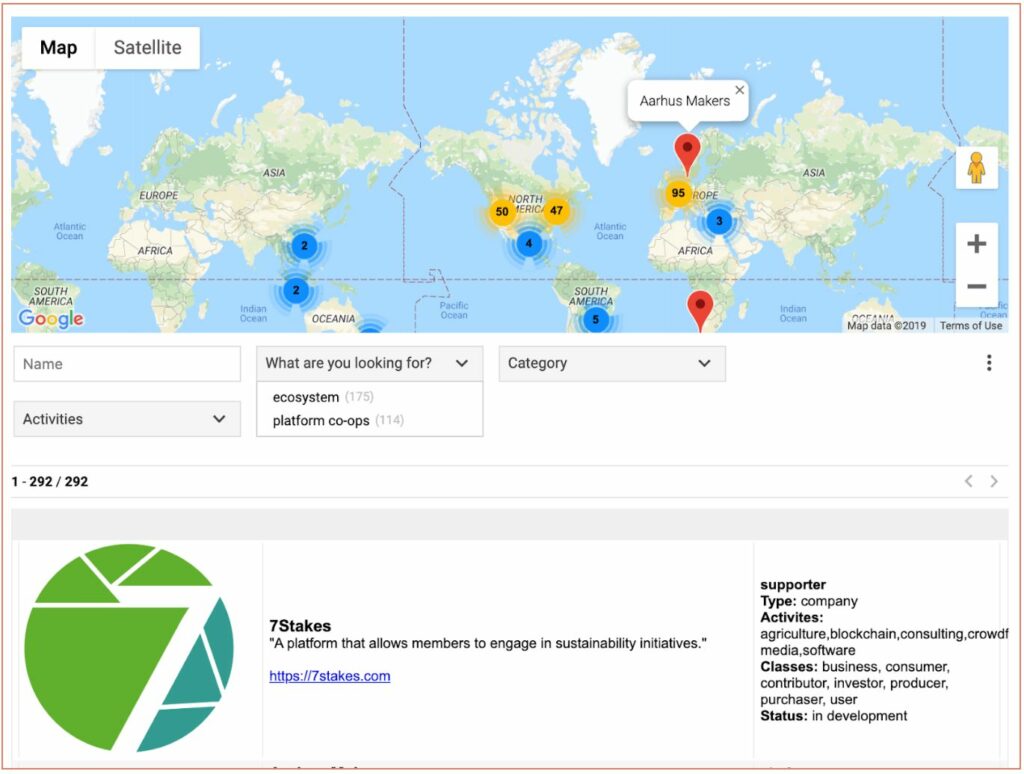

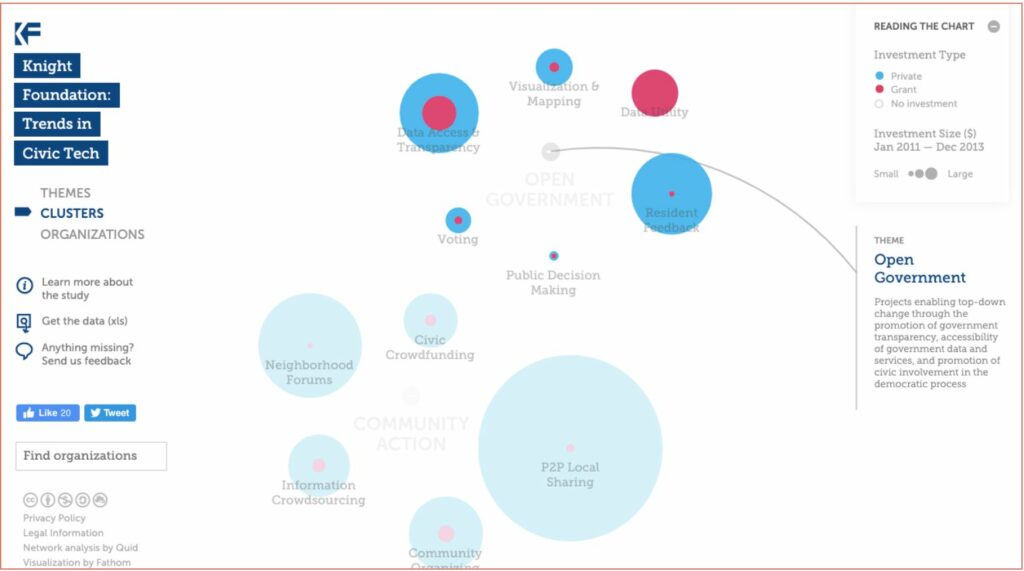

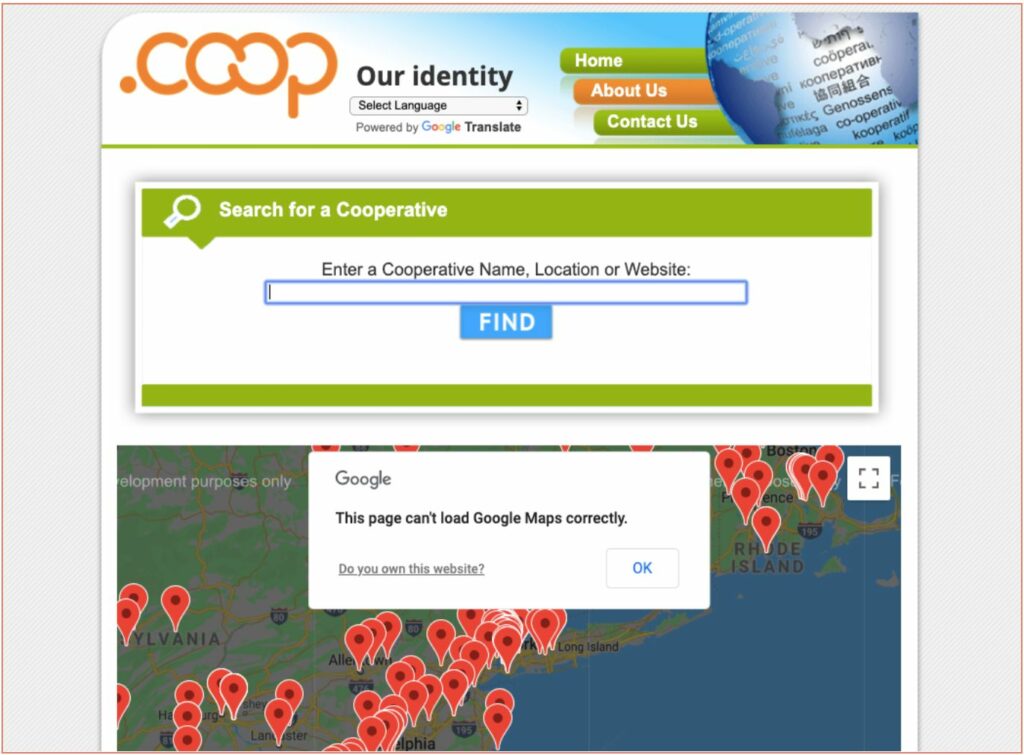

To start, I began looking at maps and indexes. I reviewed 12 examples from the cooperative movement and 6 from adjacent spaces like civic innovation. Here are a few examples:

- The most ambitious and comprehensive project so far is the Internet of Ownership (IoO) directory, initiated by Nathan Schneider at the CU Boulder MEDLab and Devin Balkind at Sarapis.org. At last count, its database includes 292 platform and ecosystem projects – some still active, others either on-pause, moved, or dead, judging by the broken links and missing logos. For comparison, Trebor cites 400 projects, but no definitive list exists.

- A map called Trends in Civic Tech, funded by the Knight Foundation, offers a beautiful, interactive database with bubbles detailing investments in various themes, clusters, and organizations – but is now six years old.

- The project I found to be the most functional was the searchable dotCoop database of websites registered with the .coop domain.

All of these maps/indexes started with high hopes. Almost all of them are going out of date or defunct. Why? The simple reason seems to be, a lack of maintenance. All digital projects deal with maintenance issues, but especially infrastructure supporting users in dynamic communities.

And yet, indexes like the IoO project are a labor of love, and maps like the Trends in Civic Tech are well-funded. Why is it that does maintenance drops off even in these efforts? The deeper reason I found is that the more people care about using a platform, the more they’ll try to maintain it – or not. Platforms need to facilitate valuable exchange among users in order to motivate ongoing maintenance. Despite its outdated appearance and broken Google Maps widget, the dotCoop database has the most current and accurate information, which I believe is the result of website managers updating their .coop domain registration during each billing cycle. We can see this principle at play in social media: people and groups that invested in representing themselves in a network will maintain their presence.

The lesson here is that without a clear way for users to exchange with one another, map/index projects fail to deliver and fall apart – no matter how much labor or funding you pour in.

However, maps/indexes are just one way people find what they’re looking for. In 2015, I talked with Sam Haddix about the struggle of building cooperative platforms and an ecosystem, too. Sam pointed me to a talk by architect Indy Johar that differentiates two approaches to system change. In the dominant approach, a group takes it upon themselves to research a space, find gaps, and intervene. In the more radical approach, that group creates conditions for others to become aware of their situation and get involved.

So, in addition to reviewing maps/indexes, I also looked at other, more dynamic ways this community has used to find and connect with one another. Here is a fairly complete list:

- An email listserv started during the 2015 conference has grown from 200 to 500 people, but is now saturated with long threads by commentators that crowd out the voices of practitioners.

- On Twitter, the #platformcoop hashtag and several accounts have been active since the first platform cooperativism conference in 2015. The IoO Twitter account regularly announces new additions to the database, and the Platform Cooperativism Consortium (PCC) account shares news and events related to its activities. A wide variety of people and associations promoting cooperatives and better platforms exists, and I estimate at least 100 co-op projects run active accounts.

- The Facebook group Platform Cooperativism – Discussion & Linkshare has over 2,300 members and has 2-3 posts per week with articles or announcements, but with no clear curation or editorial direction, posts with strategic or valuable content are rare.

- A Slack workspace used in the 2017 campaign to turn Twitter into a public utility attracted 180 members. It later opened for general platform cooperativism organizing and grew to 240 members, but has been virtually silent since August 2019.

- Finally, there is social.coop, an instance of the open social network platform Mastodon with over 1,200 members participating in democratic governance and 258 contributors donating over $4,000 annually to finance its operations and maintenance.

These options support basic awareness of people, projects, and activities, but little by way of valuable and open conversation among practitioners.

On one end of the spectrum, the email listserv is open, but flooded; people co-founding co-ops remain on the list for the occasional valuable announcement, but have voiced frustration with the constant pontification. On the other end, the Mastodon instance remains a rich but relatively niche space. And from my conversations with co-op co-founders, and observations of progress in this space over the last five years, it seems that virtually all productive communication is facilitated through personal relationships and emails. There are also countless texts, tweets, toots, and more, but to paraphrase Reggie Watts in his legendary musical keynote, “It’s all email, just branded differently.” Pushing people to a new platform won’t solve the fundamental problem of valuable, open exchange.

Based on this analysis of maps, indexes, and of other means of connecting in this community, I reframed our session: our goal was not to make a map or index of the cooperative digital economy, but to identify the opportunity for mapping or indexing it in the first place.

Preparing for the Session

Framing our day-long session was important, but just one part of the preparation. I also needed to recruit a diverse mix of participants across six stakeholder groups, invite key members of each stakeholder group to showcase their work, and organize a team of co-facilitators to help bring it to life.

Getting the right mix of participants in the room was easy in part because almost 700 people were coming to the conference, and most of them wanted a way to meet one another. Also, the Coopathon session took place the day before the opening night, so it was the only event on the agenda. On the Coopathon session webpage, I posted a basic description and include a form for people to request an invite. In the weeks leading up to November 7th, the form received almost 80 responses in the form, which asked about organization/affiliation, “A few words about your work, role, or current project,” and “What would you like to get out of this session?”

As I received more RSVPs, from co-op founders to academics, I sorted the responses into into stakeholder groups based on their situations and motivations. At the same time, I developed the format and flow for the day to serve their needs. This helped define the key stakeholder groups from the ground up, through a mix of invitations before the session and self-selection during the session itself. The result was a remix of the eight types of beneficiaries identified on the PCC website, but was still inclusive of everyone who might participate in the session and whatever map/index might emerge from it.

At least 67 people representing 41 co-op projects and 27 ally organizations, ranging from consultancies and trade organizations to philanthropies and universities.

Who Was in the Room

Around 60% of participants joined the stakeholder groups made up of practitioners, the co-founders and members of cooperative projects and enterprises:

- Emerging co-op projects, including Mensakas, Ampled, and Greenlife.

- Established co-op projects, including WMRCC Durham, Stocksy and Up&Go.

- Projects exploring co-op conversion, including Meetup and Groupmuse.

The other 40% of participants joined groups of allies, people supporting the practitioners:

- Ecosystem players, funders, and advocates, including the Indonesian Consortium for Cooperative Innovation and AmbitioUS, and CoopsUK.

- Collaborators like consultants to technologists, including the IDRC and Sarapis.

- Academics and researchers, including Leiden University, CICOPA, and Data & Society.

In terms of background, familiarity, and identity, here’s who participated in the session:

- This group of 67 also included a team of 13 co-facilitators, with backgrounds in software design and engineering, data visualization, cooperative development, and more.

- Virtually 100% of participants were familiar with modern technology platforms and concepts. Around 20% work directly in building digital technology (e.g., technologists), and another 15% do work in contexts where that technology currently not central to day-to-day operations (e.g., facilitators).

- Around 60% of participants identified as female, trans, or non-male, and 50% as people of color and non-white participants.

- Around 60% are from the US, and around 40% live and work outside of the U.S.; 25% from the U.K., Spain, France, Belgium, Germany, Serbia, and 15% from Brazil, India, Indonesia, Hong Kong, and Australia.

A lot of people who helped make the session possible were not in the room. The first draft of the facilitation plan revolved around the idea of “crawl, walk, run,” a helpful, interactive way to introduce the concept of mapping our community. I am grateful for the advice I received on workshops, mapping, and mapping workshops from Andrea Hill, Eric Knudtson, Devin Balkind, Oliver Sylvester-Bradley, John Evans/Code-Operative, and Zara Serabian-Arthur/Meerkat Media, in addition to Trebor, Michael, Cheryl, and Ned. Thanks and credit also goes to Sonja Novkovic and Karen Miner for sharing their new curriculum from the International Centre for Co-operative Management at Saint Mary’s University, which I adapted for the first two exercises.

The people who I believe deserve the most appreciation are the co-facilitators in the room: Ela Kagel/supermarkt, Eric Theise, Julia Jong, Louis Cousin/Startin’blox, Daniel Sauter/Parsons Data Visualization, Vica Rogers/Co-operatives UK, Michael Bass, Nazia Roushan/POCAA, Manuela Bosch, Nga Nguyen, Byers/CoopsSC, Travis Higgins/coonecta.me, and Olivera Marjanovic/University of Technology Sydney. Through emails and video calls, we came together to develop a final draft of the plan. Then, we helped bring it to life.

The rest of this story summarizes how the session went, what we learned from the experience, and what’s next in the process of co-designing some kind of map/index.

As people arrived, we got started with a warm-up to embody the idea of mapping and meeting each other, using balloons. First, people tried to find their own balloon, which went slow. Then, people tried to find everyone else’s balloon, which moved fast with people shouting out names, waving name tags, and having a much better time!

After getting energized and meeting a good number of people in the room, we did a couple of more substantive exercises about where people are at.

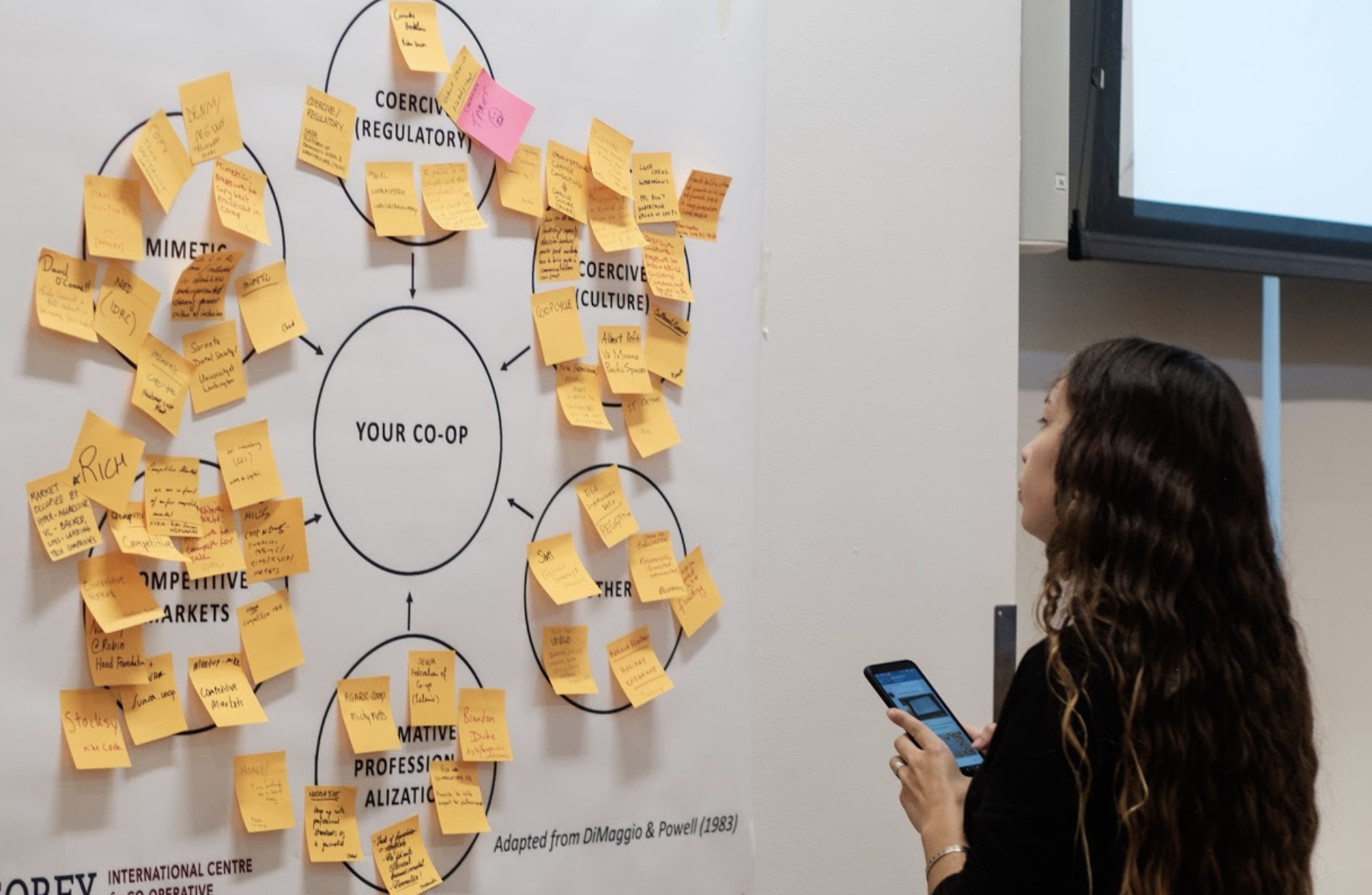

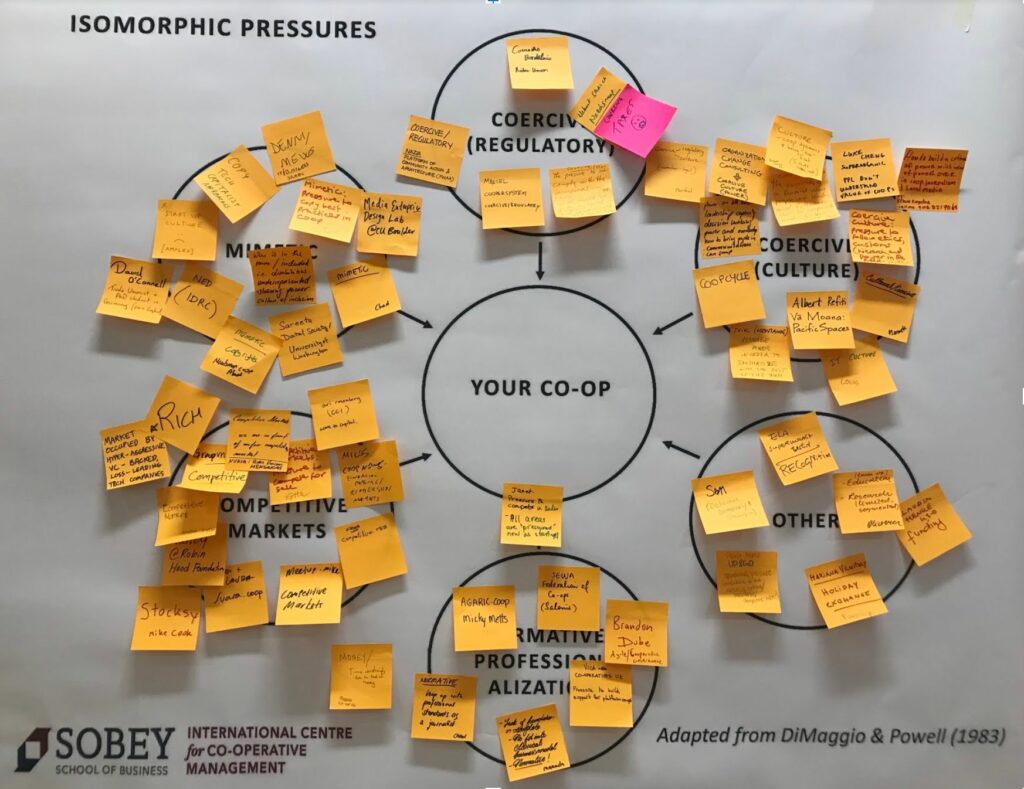

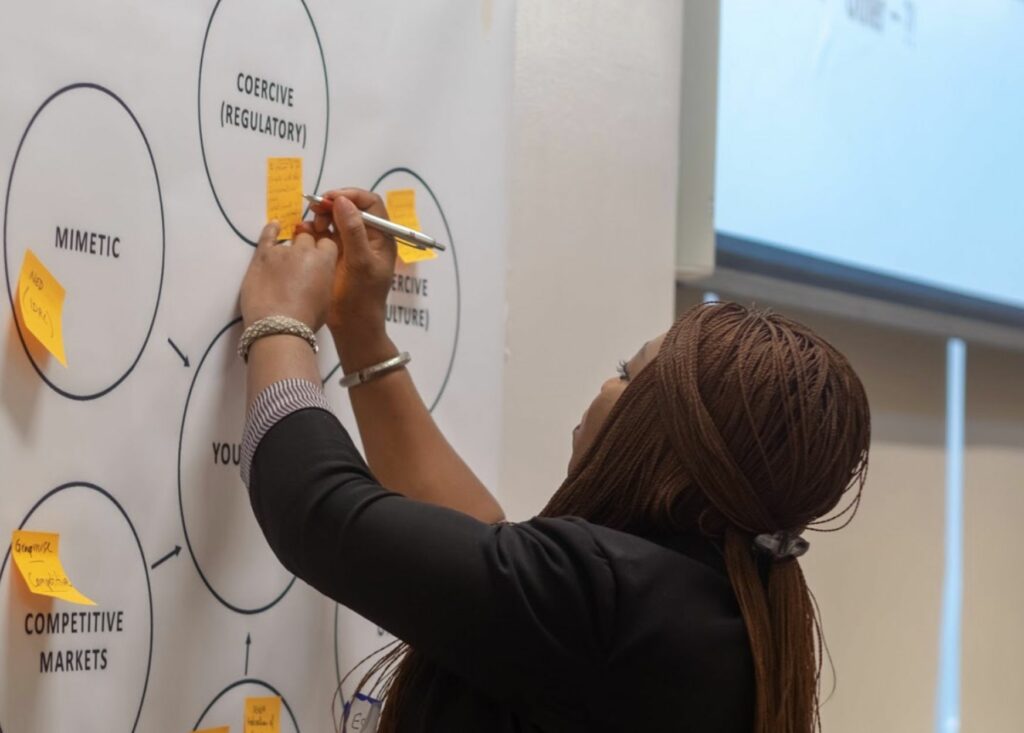

For the first exercise, we identified various ‘isomorphic pressures’ that co-ops co-founders and allies face. The co-op model is about shared ownership and democratic control, and various cultural, regulatory, and market forces threaten to make co-ops conform to more extractive models, or to simply fall apart. One example is the pressure to adopt best practices that are often at odds with the co-op model but are nevertheless hard to resist during times of uncertainty.

We hadn’t yet divided ourselves into our stakeholder groups, so people were randomly sitting with others for this ‘pair-and-share’ exercise. We each talked with someone next to us about the pressure that we’re currently experiencing the most, and then wrote our names on sticky notes and stuck them on the poster.

After the session, myself and other co-facilitators gathered feedback on this exercise in-person that evening, on Sunday in a synthesis session, and via email with participants.

Louis Cousin, former project officer at Cooperatives Europe who is currently building a knowledge base for co-op projects, saw the exercise as a good first step: “Because it was just 20 minutes, I saw this more as an ice-breaker, but it was also useful for building collective identity in common ways. ”

For Ned Zimmerman, Senior Inclusive Developer at the IDRC, naming pressures was powerful. “In the IDRC, mimetic pressure is real – unlike most designers, we don’t use personas and other things – so that really resonated.” Ned added that in terms of helping explore possible opportunities for a map/index, the academic terms in the exercise like ‘mimetic pressure’ were a bit complex. “For the future, it’s helpful to start with simple, plain language.”

But Scott Garlinger, a community manager with the classical music house show platform Groupmuse, says he and his coworker Ezra Weller came away with a lot of useful details:

“This helped tease out how our own stakeholders meet challenges in a variety of ways at a spectrum of points in our co-op journey. 2×2’s, lightning talks, and the rest do not provide enough purview for the hairsplitting distinctions required in legal code, governance structure, and internal operations.”

ari rosenberg, project director for the experimental and patient capital provider AmbitioUS, a project of the Center for Cultural Innovation, found the exercise revealing:

“Some funders take up space and make the conversation about them, but I was eager to see what practitioners identified as the common forces acting against cooperative projects. My main question was: What if capital wasn’t an issue? What else would we be able to identify?”

Importantly, ari’s view benefits from having been in a practitioner’s shoes. “This came from a place of direct experience as a co-op developer, before my current role. Ultimately, finding the money wasn’t the issue – it was getting technical assistance, legal advice, and that sort of thing.”

And yet for Esther Enyolu, executive director of the WMRCC, sustainable funding is still a fundamental factor on which so much depends for most grassroots organizations. In her feedback on this exercise, Esther told me that she was “not surprised to hear that we all share the same experience irrespective of the nature of our organizations and businesses.” She elaborated as to how and why:

“Different types of social challenges generally arise from working and advocating on structural and social issues such as gender-based violence, diversity and inclusion, gun violence, issues affecting youth and children, who are survivors of violence and abuse to working with the elderly women. WMRCC has been diligently working to bridge this gap for the past 26 years. The nonprofit is currently incubating six cooperative projects, which involves everything from recruiting more cooperative business trainers to developing business plans to facilitating incorporation. There are always threats around how to maintain programs and services in the community if funding does not come through.”

Here are two insights from this first exercise.

- Participants crave more common ground! Despite the 20-minute timeframe and academic jargon of ‘mimetic pressures’, talking about pressures exercise helped participants find common ground and share individual experiences – including first-timers in this space like Groupmuse.

- Getting perspective requires removing layers. Identifying money as one of the obvious “other” pressures helps get it out of the way for established projects like WMRCC to focus on other, more fundamental pressures, a key concern for grantmakers like AmbitioUS.

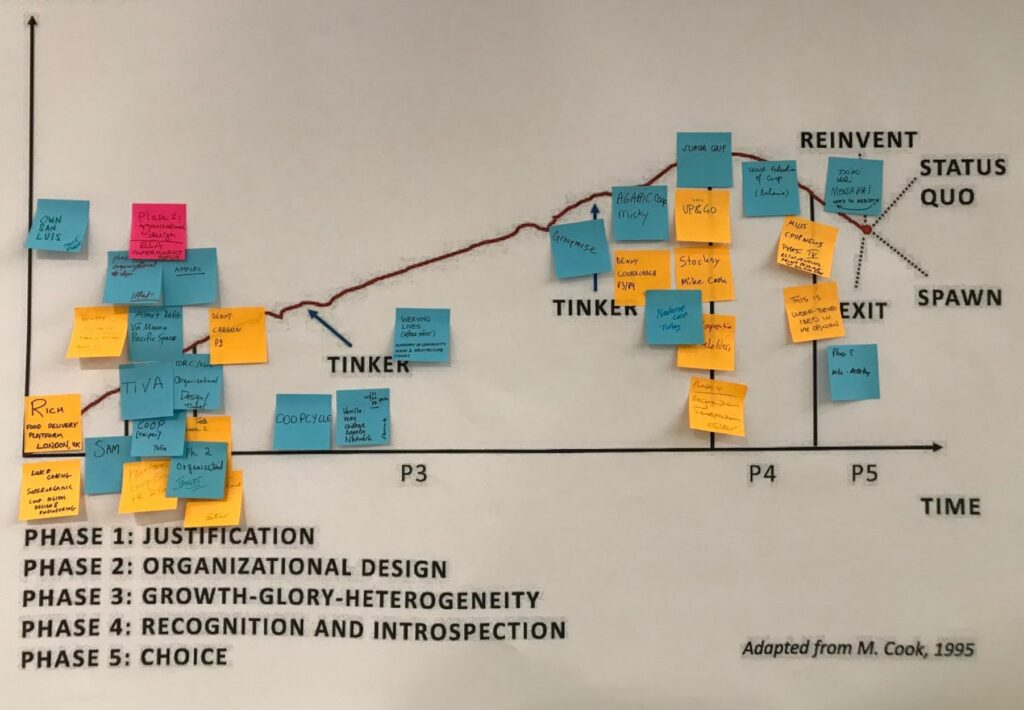

For the second exercise, participants did another pair-and-share about what phase they’re at in their development lifecycle.

Finding common ground depended largely on stakeholder group and conversation partner being a practitioner. Ned appreciated learning about the UK-based Co-operative News: “In talking with Miles [Hadfield], his organization had been around 150 years and is transitioning from print to digital, so we had a really hard and fascinating conversation about reinvention.”

Scott from Groupmuse found this exercise particularly helpful, thanks to comparisons with peers in a phase of reinvention:

“Identifying our phase of development was at once a normal discussion, and an exceptional one. Normal, because we presented our circumstances in a tried and true manner. The response, however, was something I’d never heard before: that most conversions occur in a ‘reactive’ setting (where the workers buy out the company when a fire sale takes place and things are hitting the fan). Proactively converting would be an exception (it would seem). Thus, our path to conversion must seek out more lonesome models than some of the more practiced ones.”

Similarly, Louis shared his surprise at the depth of conversation based on the idea of the justification phase:

“In talking with Nuri from Mensakas and Esther from WMRCC, we had a lot of in-depth, rich content. The most important points emerged when we realized, ‘We are not in the same sector, but we have the same challenge’ like buying a building, expanding to digital platforms, and so on. We agreed that any co-op needs to establish its business model before imagining the role of a platform, not the other way around. For example, CoopCycle is building an app, but that is not foreseen as their basis for revenue.”

In contrast, Manuela Bosch, a Berlin-based collaboration practitioner, found it difficult to engage. She realized that “my subconscious was inspired, but it didn’t logically help me.” Manuela consults with co-op and democratic projects, and this exercise was difficult to apply to her own work as an ally. She added, “I wonder how relevant this specific is for academics and collaborators” – in other words, not very.

Julia, a co-facilitator for the group of emerging co-op projects, said that this exercise was even more motivating than the first in terms of urge to engage across the entire group:

“Everyone was excited to start sharing out with the people around them. One person I had the opportunity to check in with reported feeling the conversation had been listening to just one narrative and he wanted the chance to engage with other people.”

But one point really stuck, about a desire to go deeper. Édith Darin organizes with CoopCycle, a France-based federation of bicycle courier co-ops building software, licensing, and more. She said what many of the other co-op projects said, too:

“I enjoyed stepping back from our individual experience and realising that we have a lot in common with projects that in appearance were really different. It was unfortunate that we couldn’t speak longer on the problem per type to see how others circumvent it… Maybe not enough time was allocated for actually speaking about the issues that were raised, but in a sense a good introduction for the following days!”

Here are two insights from the second exercise:

- Discussing co-op struggles is easier in plain language. Even with only 20 minutes for this exercise, the use of “lifecycle phases” helped people in pairs and in groups find themselves in meaningful conversation about major changes for co-ops, from the brand new CoopCycle to the 150 year-old Co-operative News.

- Focusing on real co-op projects helps everyone connect. Manuela, an individual collaborator and co-op ally found it hard to relate with her own work, whereas other allies like Ned and Louis found it easy to go deep in listening to co-ops projects.

Now, to evaluate the two exercises in our session so far:

- The test: To help participants bring their experiences into the room and build shared identity, we explored projects in terms of forces and phases.

- The results: Participants got excited about naming common struggles and connecting with peers, which Édith of CoopCycle said was not enough time, but a good start.

- The lessons: Plain language helps people connect quicker, and we need more time and interaction beyond what 20min makes possible.

After a break for lunch from Khao’na Kitchen, a vegan/plant-based catering and wellness collective, we organized ourselves into six stakeholder groups for a longer, in-depth exercise.

This third exercise was a group activity that provided the backbone for our session: co-creating an empathy canvas for each of the six stakeholder groups.

To start, one individual in each stakeholder group shared their story. A facilitator asked them questions about where they’re at, what’s going well, and what they’re struggling with, and more to create a space for them to share their narrative and insights. Another facilitator wrote notes on sticky notes for the empathy canvas on the table. The prompt was for everyone to listen deeply to the first story to hear if their own situations and motivations were represented. After about 30 minutes of listening patiently, other members joined in, asking their own questions writing their own notes, too. Then, they began sharing their own stories, too. The exercise ran for 90 minutes, and was still not enough!

This exercise was an experiment in balancing complex stories and details with simple understanding and quick satisfaction for listeners. This was most obvious in the group of established projects, especially listening to Esther share the 25 year-old story of WMRCC. After decades of service, the WMRCC has been expanding their scope from working with immigrant women, youth and children, and victims of violence to working with the elderly and entrepreneurs among these populations. The nonprofit is currently incubating six cooperative projects, which involves everything from recruiting more cooperative business trainers to renting a space for the co-ops to operate. WMRCC’s expansion also involves changing their notion of success, an essential nuance.

Nazia, a co-facilitator with the established co-op projects group, described how Nga, another co-facilitator, created space for that nuance in their in-depth conversation with Esther:

“It took a split second more compared the other answers for Esther to tell us the WMRCC’s measures of success. She said that if the coops can become established coops, that will be their success. When asked how do the women in the coops measure success, Esther thought for a bit and said, ‘by making money.’”

Similarly, in the emerging co-op projects group, Julia and Ela co-facilitated a conversation with Nuri Soto and Txiki Blasi of Mensakas. Julia described the results in terms of a complete narrative arc, from challenges to peer support:

“One concern the Mensakas members have is finding a market for their work that can provide a sustainable living. Working as subcontractors now, they have to compete with commercial apps and services that have more resources to develop and maintain their platforms. Also, working as subcontractors limits their visibility. They see an opportunity to provide delivery services for farms, and to do deliveries for more vulnerable populations such as the elderly, for whom they can provide social check-ins as well.”

Julia also points to requests for support and responses from peers:

“The primary support they are looking for is knowledge of economics and how to build a business strategy that is right for them. One lesson they have learned during their process was the value of working with other groups (which they initially shied away from). Ultimately, the conversation with Mensakas inspired many members of the group about the power of narratives in connecting coops.”

Mike Bass from Meetup.com, the online platform that helps people organize events offline, appreciated the in-depth interview in the group of stakeholders exploring co-op conversions: “We only had one, or maybe two people talking from Groupmuse. The rest of folks in my group were there to listen and learn.”

However, not every story spoke to everyone around each table – and not every nuance resonated with everyone, either. Nathan Schneider participated in the collaborator stakeholder group. During the synthesis session, he said, “our group was full of active infrastructure builders. I felt ready to start discussing plans for action. But, I heard from Austin Robey [co-founder of emerging co-op Ampled] that listening to Mensakas in his group was his favorite part, taking it all in.”

Not all stories are relevant or useful to everyone! Byers pointed out that in the three practitioner tables decided to break into side conversations. In fact, towards the end of the exercise, a group of five people who knew each other previously and wanted to reconnect left the six stakeholder tables and set up a seventh circle of chairs.

The role of allies in relation to co-op practitioners came up for everyone, but especially for the academic. Olivera Marjanovic, a professor at the University of Technology Sydney and currently building industry-wide Visual Atlas of the Australian Cooperatives, participated in the academic stakeholder group. In Olivera’s words:

“The empathy canvas ended up working really well for us, even though it was initially perceived as somewhat unsuitable for our group of academic stakeholders. Data came up in our discussion again and again, in relation to different aspects of research. For example, we observed the need to collect and share more data on platform coops: Where and how to collect data? What kind of data? How to make this imagined index also useful for researchers, not only practitioners.”

Here are four insights from the empathy canvas exercise:

- Nuance takes time and space and focus. Helping practitioners get to the nuance in their projects was possible due to the in-depth conversation format, the interview skills among co-facilitators, and the comprehensive coverage of topics on the empathy canvas. For Esther, it helped her see success for the WMRCC co-ops as “making money.”

- Representation many ways to engage. For everyone to feel heard and to be included in the empathy canvas, it was essential to for people listening to interact, like adding sticky notes based on interview responses or asking questions based on personal interests.

- Practitioners are best suited to serve themselves. The practitioner stakeholder groups made new ways to engage throughout the exercise. Austin from Ampled was captivated by what Mensakas had to say, and Mike from Meetup noted everyone listening intently to Groupmuse, but some people split off into new side-conversations or entirely new groups, as they found new individuals worth meeting or other topics worth discussing.

- Allies are most productive when they follow practitioners. The ally stakeholder groups also found ways to engage effectively. Nathan and other collaborators craved more co-creation in their group, while Olivera and other academics situated their group’s needs within the broader ecosystem and its needs.

Now, to evaluate the empathy canvas exercise overall:

- The test: To help stakeholders represent themselves, we ran empathy canvas exercises that started with in-depth interviews and then including other input.

- The results: Practitioners (and to a lesser degree, allies) appreciated feeling heard as well as hearing others, both in group interviews and one-on-one conversations, and several like WMRCC made concrete progress in analyzing their situations.

- The lessons: Creating ways for practitioners to interact with structured case studies or open-ended chats can open space for more of what participants said they wanted: more advice, resource sharing, and connections. Expanding the exercise to include customers as stakeholders could have helped co-ops explore market dynamics.

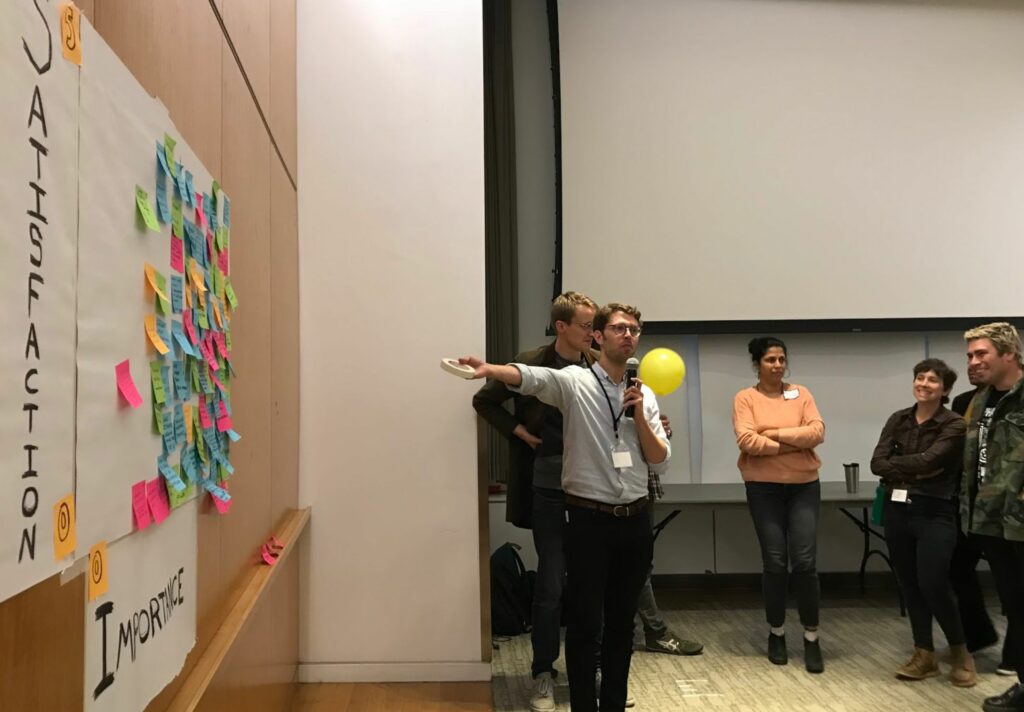

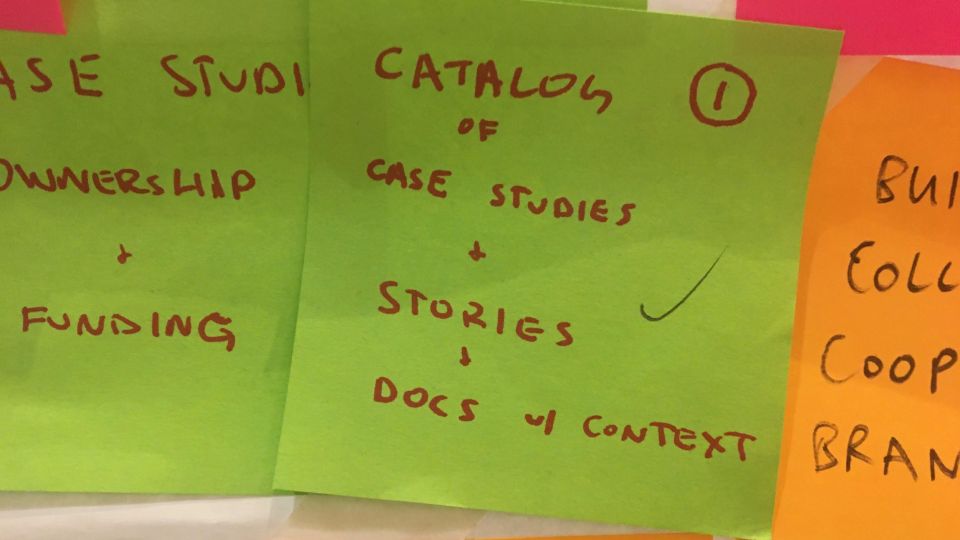

Finally, to get a collective view of our community opportunities around mapping/indexing, we closed the empathy canvas exercise by asking each stakeholder group to write sticky notes with opportunities they saw to connect over the coming 48 hours. Each group put their notes on a graph according to level of importance and level of satisfaction with current options. Then, we had the big reveal: identifying the well-served needs which called for disruptive innovations – like “legal template documents” or “converting politicians to cooperativism” – and the under-served needs which called for breakthrough innovations – like “learning from indegenous modes of cooperating” and “keeping connected after 48hrs.”

Julia reported that in the group of emerging co-op projects, “many of the ‘opportunities’ people were asked to write out for the Importance-Satisfaction graph were to share more of the stories or case studies for others to connect with.”

Clearly, there was a desire to learn and share beyond what a half-day session made possible. In the synthesis session on Sunday, Ned highlighted a similar point: “It seems to me that people crave a more dynamic communication tool, more than a static directory or a clunky email listserv.” And Nathan, who helped start the IoO directory and has been in virtually all of the communication platforms as an ally, brought that point to life: “Everyone co-founding a co-op is struggling under scarcity. So, having a carefully curated forum for practitioners, with clear focus and intentionality, could help make taking the time to collaborate feel more valuable to them.” Indeed, the platform cooperativism conference has been the best place to meet and connect with people, and even so, it’s been mainly at breaks between panels and presentations.

And yet, our session modeled some of the key exchange people are looking for. A few people left with more than enough for their interests. Scott from Groupmuse was particularly satisfied:

“Walking away from the workshop opened me up to the nested worlds of co-op production. It gave me a fresh impression of its history; a working group of colleagues who are pursuing the same goals; and action steps to understand what’s needed for Groupmuse to convert.”

To evaluate this concluding exercise:

The test: To help participants prioritize needs as a community, we ran an exercise for each stakeholder group to graph opportunities they saw for the two-day conference and beyond.

The results: Participants shared an extremely diverse and varied set of responses that blur the line between opportunities and needs. However, we can see clear patterns: they care about large historic trends, small tactical concerns.

The lessons: Presenting current options or future ideas for what we as facilitators assume are real opportunities and core needs helps participants offer more clear and focused feedback. Co-creating and testing these ideas might prove more satisfying, too.

What We Learned

Our session taught us a lot about mapping and indexing, and we have much more to process. Manuela digitized the entire graph of sticky notes for needs and opportunities, and Julia sees ways we might analyze those and the sticky notes from the exercises on forces and phases to connect the dots and find interesting patterns. There were shortcomings in how I set up our session that need to be revisited and improved upon, from including second-order stakeholders like any customers who only shop for co-ops to facilitating more co-design of map/index ideas.

But thanks to active community members and committed co-facilitators, and after processing the observations and feedback from the session so far, we’ve synthesized key lessons for the future of this project to map/index the cooperative digital economy.

1) Creating container for serendipity

Holding space to meet others is something we rarely do for ourselves. The serendipity of being with peers we might want to meet yet is rare. And if we aren’t in the same room, can feel almost impossible. However, participants tuned out of conversations when the story doesn’t include them. We saw this during the in-depth stakeholder interviews when peers seemed to stop listening, and when they started new conversations with their neighbors.

Simply creating a space for our community to come together and connect was a valuable stepping stone towards making some kind of map/index. The framing we used for the session and the insights we came away with got us several steps ahead, too.

2) Putting practitioners on the map

Two requirements make for more productive mapping/indexing of the cooperative digital economy: 1) talking with co-op co-founders, and 2) focusing on cooperative projects. The importance of centering practitioners dawned on many participants in each exercises, and is obvious from this synthesis, too. Conversely, without practitioners at the heart of the conversation, allies who might be more accurately labeled as “pontificators,” to use one participant’s term, tend to dominate and crowd out others. We’ve seen that in all of the past communication platforms and far too many email threads.

Throughout the last few hundred years, and in the past five years, too, co-op co-founders have taken collective risks to provide for communities that weren’t served by markets. So, at the very least, centering and re-centering practitioners makes for more interesting stories.

3) Highlighting specific common experiences

Stakeholders have two broad interests in mapping/indexing this community: stories and trends.

First, practitioners such as want to go in-depth with story and data from peers. As Nathan said, people in this community “tend to vilify ‘founder culture’ but also tend to not honor [or reward] the sacrifice that co-op co-founders make. Some struggle for years to start something, like Jen Horonjeff from Savvy who, after years, is finally going to start paying herself.”

Second, allies and others building or studying the ecosystem want to go broad. Trebor told me that in his experience organizing these conferences and advancing the idea of platform cooperativism worldwide, would-be allies like policymakers and grantmakers are primarily looking for numbers and trends, and are also curious to know if any projects exist in their geographic or political areas.

Serving these two interests can be done by highlighting specific common experiences, like the “key points” shared in the exercises on the forces acting on co-ops or the phases of development. Those points helped participants get just enough information to stick with one conversation or search for another, and in aggregate, they can be used to find trends, shared needs, and more.

4) Curating conversations around case studies

Finding useful information is often easier in conversation with others. Byers, who advocates for co-op policy in her city, gave real-life examples. “A reference librarian knows so much, and they help you search. Or, talking to my dad when I’m having a hard time, I might start the phone call in chaos and by the end, I know what to do.” And as we saw in our session, many co-op practitioners can relate to the positive experience of a deep conversation.

Connecting many conversations is what makes for a community, a movement. Louis shared his experience with Cooperatives Europe: “We worked with the Belgian federation of co-ops, they go around and do workshops, and it’s hard to share and spread what we learned. How might we connect this workshop to the next workshop? How might they build on each other?” One idea: workshop facilitators fill in a database on topics like ‘co-op legislation’ so that past and future participants can become beneficiaries of the knowledge in a more structured way.

For a community to map itself, it needs to balance finding information and connecting with people. Even the most beautiful visualizations can’t help people connect if there’s no contact info! Curating online conversations has a struggle so far, but there is a lot of promise in ideas to create in a dynamic communication platform around case studies.

5) Shaping expectations for all stakeholders

Making a map/index is easy. Making a map/index that people actually use, however, is hard. And creating a map/index that connects people to one another is even harder.

One reason for complications is the way data gets centralized among a few individuals that become either bottlenecks or gatekeepers. Ned described one theme he heard in the session and in previous research: “Some people seem to care a lot about the ‘centralization’ of data. We [the IDRC] could work with the ecosystem and get good semantic data and aggregate it with, say, schema.org” which is no small task. Nathan agreed and said people fail to realize that “decentralization is easier said than done, and the community may not have the bandwidth to co-create. An accountable but centralized approach seems more likely to work for now.”

So, given the challenges of mapping/indexing and the complexities of data models, it is essential that we set careful expectations for all stakeholders as this project moves forward. Each of the six groups described their situations, and their needs: money, the things that money makes possible, and more, from inspiring stories to legal templates, all with dynamic communication and curated conversations.

Conclusions and Directions Forward

“I am struggling to see how we handle all stakeholders,” Cheryl said in our synthesis meeting.

Our session was full of potential, but very complex. Still, we came away with solid conclusions and promising directions forward.

First, we agreed that sharing prototypes with the community in a responsible and accountable way is now within reach. Over the course of this session and the preparation leading up to it, we had reviewed many inspiring, stalled, or failed maps/indexes, and found a new view of shared needs and opportunities among stakeholders who also really enjoyed their time together. We used our synthesis meeting to document what we heard and learned, which became the basis of this report. We also devoted time to discussing how we want to be in relationship moving forward. Cheryl said, “I’d love to adopt some cooperative governance.”

So, going forward, we will form and strengthen more of these relationships. And as we do so, we’ll also have more outputs from our time together, including:

- Illustrated summaries of situations and motivations for each stakeholder group.

- Data visualizations based on what people shared about forces and phases.

- Video testimonials that might also be used in early map/index prototypes.

Second, we discovered ways that community efforts might dovetail with a map/index. For example, Louis shared a sneak peek of a co-op knowledge base that is being live-tested. He said it emerged from conversations with “young cooperators who don’t have any money to come conferences in NYC, but are really talented and deeply familiar with the same issues of communication when they try to share experiences, find each other, adopt innovations, represent ourselves to big federations” and so on. The knowledge base has many parallels with the workshop exercises on forces, phases, and data about co-op struggles. It is also building a semantic data model for representation, something Ned saw as a key theme in our session.

With efforts like these in mind, the IDRC will continue to dig into what we learned and start co-creating ideas for feedback. They will begin their iterative design and development process some time in January, 2020. And now that we have a useful framing for a mapping/indexing project that supports communication, it will be easier to partner with communities like the one that formed in our session and with promising projects like this knowledge base.

Third, based on the session, we see a future for this project. Perhaps the best takeaway is what Cheryl said as we left the synthesis meeting. I asked her how she felt, and Cheryl said, “Compared to before, I’m much more optimistic about being able to build something.”

What’s next?

In January 2020, Cheryl Li and Dana Ayotte, two members of the IDRC’s Platform Co-op Development Kit team, will begin the co-design process to prototype the index. They are looking to co-op practitioners for insight on how the index might help people to connect through shared experiences, and how the index can highlight relevant case studies.

To get updates on the project or to be included as a participant in this process, please get in touch with Cheryl and Dana by filling in the form at tinyurl.com/coopdevkit.